By Sara Bongiorni

Build Baton Rouge is conducting a first-of-its-kind experiment in urban redevelopment. It’s incubating a hybrid land bank and trust to advance the redevelopment of blighted lots on and near Plank Road into affordable housing, parks and green spaces, commercial sites, and environmental services.

Foundation Fact: The Baton Rouge Area Foundation researched and created the parish redevelopment authority with participation from local government. A Foundation representative sits on Build Baton Rouge’s board.

Plank Road Community Land Bank and Trust is a 501(3)(c) nonprofit that will work with Build Baton Rouge to implement its plan for an area that for years has been a focus of BBR, the East Baton Rouge Parish redevelopment authority.

In time, the trust could be used to drive investment in services from job training to grocery stores in long-neglected neighborhoods in the Plank Road corridor that include some of the poorest in the nation.

The structure and operations of the trust include several novel aspects.

For starters, it will not sell land outright. Instead, it will hold land in perpetuity while making lots available for housing and other development through long-term leases of up to 99 years. Houses and other land improvements will be bought and sold separately from trust-held lots on which they are built, with sellers keeping more equity the longer they stay.

The model restricts a home’s sale price each time it is sold to keep it affordable for other low-income families. A resale formula and other operating policies will be developed in coming months by the new organization’s board in cooperation with a community advisory panel.

The pocket park will be near a bus transit stop and other projects meant to goose revival.

The shared-equity approach balances the opportunity for residents to build intergenerational wealth with long-term housing affordability. Prohibitions on quick flips will likewise promote neighborhood stabilization and prevent displacement and gentrification as the area draws new investment.

“This is largely about affordable housing but also community well-being,” said Manny Patole, project manager for Co-City Baton Rouge, a New York University and Georgetown University initiative to support area reinvestment in collaboration with local partners.

Patole has worked on the project since 2018 with professors Sheila Foster of Georgetown and Clayton Gillette of NYU. Baton Rouge partners include The Walls Project, Metromorphosis, LSU, Southern and activists working to advance the Plank Road area.

The new entity’s first land acquisition highlights operations that will reach beyond affordable housing, the traditional focus of community land trusts. In coming weeks, a 10,000-square-foot lot at Plank and Erie Street will be transferred to it for development of a pocket park that eventually will be managed by BREC.

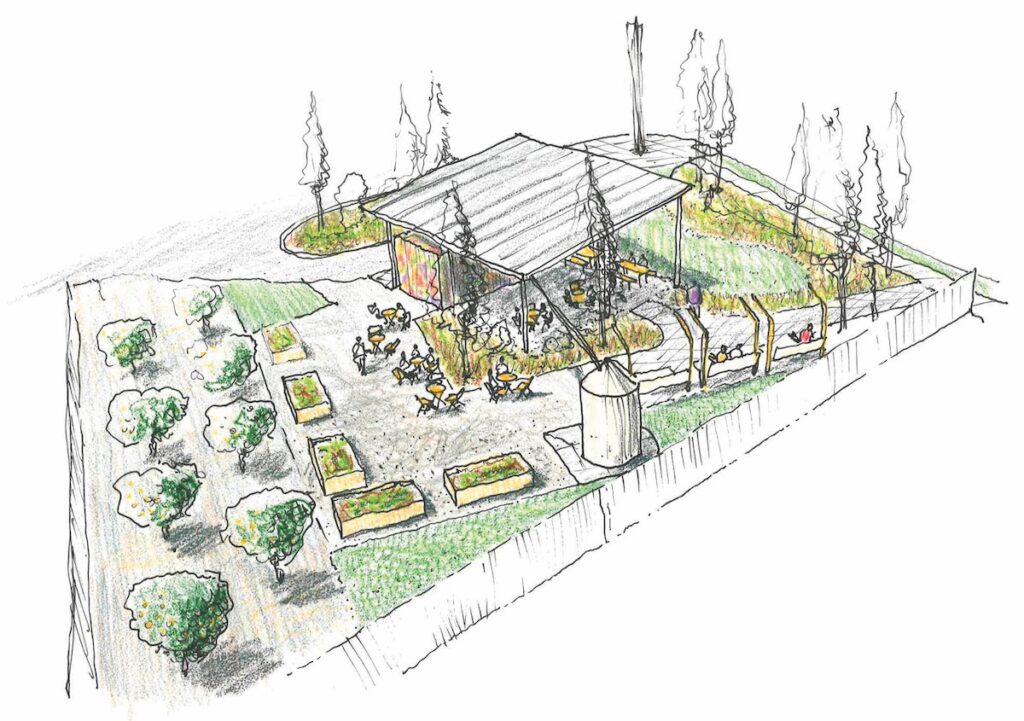

The Erie Community EcoPark will include elements determined through a community engagement process, such as a community garden, shaded seating, public art and stormwater management to mitigate flood risk tied to climate change. A Plank Road bus stop for a rapid transit line will provide efficient connections to Florida Boulevard and Nicholson Drive.

Broadly speaking, public land banks are better at acquiring land, while trusts are better at activating it for community benefit. The hybrid organization taps into the advantages of each by combining them into one entity.

BBR acquires tax-delinquent property, mostly vacant lots, through an adjudication process that involves city council approval. But cloudy title issues can require tens of thousands of dollars to resolve and hold up plans to return vacant property to active use.

Going forward, BBR will transfer Plank Road-area properties into the new trust, a step that will start the clock on a 10-year period to resolve titles automatically.

A new park on Plank Road is part of a renewal project

Initially, about 40 lots will be moved into the trust. BBR will continue to transfer Plank Road-area properties to it unless it has earmarked them for a specific use, said Gretchen Siemers, director of planning and special projects.

From there, the new trust will work with developers undeterred by potential title issues and nonprofits looking to build housing and other projects in line with organization priorities.

“It doesn’t provide immediate relief, but in the meantime, if we can put them in a nonprofit land trust that will care for the properties and look for ways to activate them with community input, then that’s a win-win for everybody,” said Siemers.

The trust also will accept property donations and purchase land when feasible, she noted.

An interim board of local leaders and community advocates will expand to a permanent 15-member governing board over the next several years.

The community advisory panel is also still in the works. It will offer an opportunity for collaborative governance in a neighborhood where many have deep-seated mistrust of public agencies.

“This is a way for people to engage in a way that is meaningful to them,” Siemers said.

The entity’s formation marks a shift to implementation of the Imagine Plank Road: Plan for Equitable Development, funded by JPMorgan Chase’s Advancing Cities award and the Huey and Angelina Wilson Foundation. Its development is grounded in 18 months of legal and institutional research that looked at best practices in cities like Atlanta; Albany, New York; Richmond, Virginia; and Roxbury, Massachusetts.

JPMorgan Chase and the Wilson Foundation have been important supporters of work that draws on the idea that community pride grows out of community participation and neighborhood governance.

Among the findings: There are no fully operational hybrid institutions like the Plank Road model. “This would be the first of its kind in the U.S. and possibly globally,” Patole said.

It’s worth pointing out what the new entity won’t do, including appropriate land or require a landowner to move a property into the trust. “This is an institution for community empowerment,” Patole said.

The organization will incubate in space provided by BBR until it is ready to set out on its own with a staff that it will recruit in coming months.

Patole estimated that it will take five years for the organization to get fully operational. In time, he hopes it will become a model for reinvestment in other parts of Baton Rouge, too.

“This is proof of concept that will start here and grow,” he said.