By Sara Bongiorni

The Gardere Initiative runs summer and holiday camps and an after-school program from a homey Ned Avenue fourplex that serves as the neighborhood’s de facto community center.

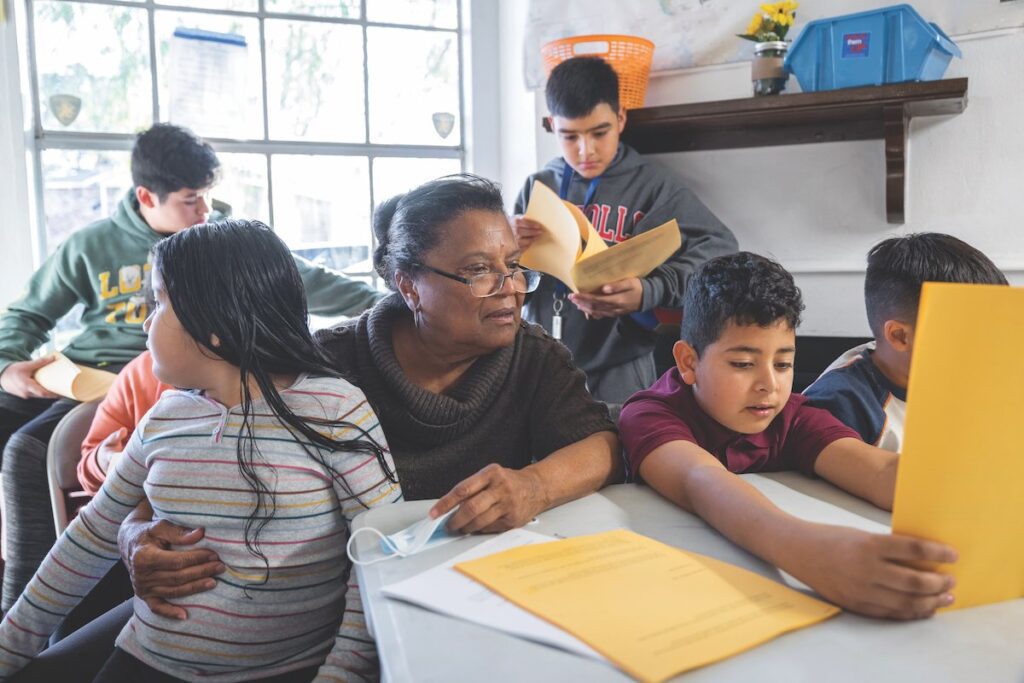

Murrelle Harrison makes sure the neighborhood kids learn and enjoy their lives. | Tim Mueller photo

The grassroots organization has made an outsize impact in an unincorporated part of the parish that battles crime and poverty. It has done it on a shoestring budget with a paid staff of two and volunteers from community partners and churches that helped get it started 15 years ago.

It got sidewalks built on the east side of Gardere so residents don’t have to walk in the busy road—it’s pushing for sidewalks on the west side, too. It organizes litter clean-ups and prayer walks. It partners with the nearby sheriff’s substation to create trust and combat crime, which has dropped sharply since a particularly violent period after Hurricane Katrina.

It partnered with BREC to build Gardere’s first playground and transform what used to be a grassy field into 14-acre Hartley-Vey Park at Gardere with a lighted basketball court, paved walking loop and three sports fields.

The well-being of Gardere’s children is paramount. The initiative arranges swim lessons at Crawfish Aquatics for elementary and middle-school children as part of its free eight-week summer camps. About 100 children take part in the camps, which include components focused on math and reading and art activities run by the LSU Museum of Art, an important partner.

Giving kids a safe and welcoming place to go is essential, but so is creating opportunities for healthy fun in a neighborhood that used to be what Executive Director Murrelle Harrison calls a play desert. Recent outings included a holiday party with man-made snow and an evening of roller skating and bowling at Mount Pilgrim Baptist Church. The Scenic Highway church also understands the value of fun. It loaned the Gardere Initiative its skating facility, bowling lanes and as many of its 75 pairs of skates as it needed.

““It is using money wisely to make a difference in this community. It’s what everybody is searching for.” ”

— JAMES VILAS, GARDERE INITIATIVE CHAIR

The Gardere Initiative relies on borrowed church vans to transport the kids, but it hopes to get its own van this year after receiving $9,000 through the 225 Gives community fundraiser.

“Children need a chance to run free and just be kids,” Harrison says.

There is a free library outside the Gardere Initiative offices. Inside are resources as different as board games for children and job assistance to help with English. The latter has become increasingly important as Honduran families continue to move into the area, a shift driven by a wave of construction work caused by the historic flooding of 2016.

Flyers and social media posts are bilingual in recognition of the rearranged demographic that includes adults and children with little or no understanding of English.

There is no set daily schedule other than the afterschool program. Someone might drop by to use the copier or just to say hello. After the pandemic closed schools, children who otherwise would have been home alone came to play board games. Teens without Internet at home completed assignments using the Wi-Fi.

On a recent morning, the staff was arranging to get a belt and school uniform for a high school student who did not have them.

A federal drug prevention grant covers the rent and the salaries of the initiative’s two staff members, but Harrison, a semi-retired Southern University professor, hasn’t taken a salary in eight years. The Huey and Angelina Wilson Foundation also provides support for Gardere Initiative programs and services, all of which are free.

The organization started in 2006 with a back-to-school event and a yearly celebration called LoveFest. Over time, Harrison realized it needed to have an ongoing presence in the neighborhood to have the impact it wanted.

An abandoned unit in a fourplex caught Harrison’s attention. It was in rough shape, but it was also next to an undeveloped BREC park. Nobody had money for repairs. The owner took up Harrison on an offer of 40 hours of volunteer work for some free rent. The organization moved to the renovated unit in 2014 and started knocking on doors to meet its neighbors, still a preferred way to connect with nearabout families.

A visit to Ned Avenue on a rainy Thursday afternoon offers a glimpse into the organization’s place in the lives of the children who tumble into the front room with happy excitement after bustling off buses that drop them off out front.

The children from pre-K to sixth grade get a substantial snack—on this day, chicken nuggets—before they are grouped by age and whether or not they have homework. Children who don’t have homework spend some time reading nonetheless, as part of either a group book or a more informal gathering of older children to discuss events in the news that capture their attention, Harrison explains.

“We stress reading,” she says.

The park is integral to the organization’s work. A $15,000 grant from KaBOOM! paid for a playground that community members helped to design. BREC then invested $350,000 in improvements that include the walking trail, covered picnic pavilions, a regulation-size basketball court with lights for evening play, containers for a neighborhood garden and 25 young oak trees.

The park will get free Wi-Fi in 2022 with help from BREC and Cox Communications, which has provided Internet and other services important to the afterschool program.

The organization uses the park to maximum effect in support of both children and grown-ups. Its 14-team adult league with 300 players uses its three sports fields on Sunday afternoons. Its youth football program is held there. Taking the kids to the park so they can run around after a day at school is part of the Monday through Thursday afterschool program.

The park may play a bigger role yet as the organization looks ahead. The chairman of its board, attorney James Vilas, dreams of building a BREC soccer stadium at the park that could include space for the Gardere Initiative.

It’s too early to say how and when that could happen, and it’s not the only idea being considered as the staff and board mull the organization’s future.

More room would allow the Gardere Initiative to provide more help to families. Harrison envisions a “one-stop shop” to connect families with food assistance, classes and legal help. She notes that neighborhood children sometimes miss school to accompany their parents to meetings with local agencies to serve as translators.

Summer camps also could be extended to full-day from half-day with more space. Campers now rotate between the park and the small rooms in the Ned Avenue building, where there is not enough space to accommodate all the children at once.

A satellite location of the public library is something else Harrison thinks about. Even with sidewalks along Gardere, it’s a long walk to the Bluebonnet branch—the closest library.

Recent renewal of its federal grant will provide funding through 2026, but Harrison says thinking about hiring a paid director is another part of planning for the future.

“I’m 73,” she says.

For his part, Vilas is working to raise the Gardere Initiative’s profile. He helped create an online link for donors on its website. It also became its own IRS-recognized nonprofit a few years ago. A first-generation American who speaks Spanish, Vilas says the more people know about the organization, the more they will want to help.

“This is about getting kids off the streets while their parents are working six and seven days a week for their families,” Vilas says. “It is using money wisely to make a difference in this community. It’s what everybody is searching for.”