By Mary Ann Sternberg

On the concrete T-head of the old Baton Rouge municipal dock are now-fading words in white paint of John Lennon’s famed song “Imagine.” According to local lore, this graffiti appeared soon after singer and spiritualist Lennon was killed in 1980, when a devoted fan (one of many adventurous trespassers) sneaked out to the end of the dilapidated wharf. She would have had to climb the levee, trod a rotting wood bridge and thin, corroded metal platform, and shimmy through a locked metal gate, to emerge into a rusted-out metal shed with walls so vibrant with colorful graffiti that an artist compared them to stained glass windows. It was here Lennon’s acolyte scripted the lyrics.

Though the words actually referred to world peace, its commandment could as easily have been interpreted as the mantra for what to do with this riverside white elephant that had once promised to transform Louisiana’s state capital into an important inland port.

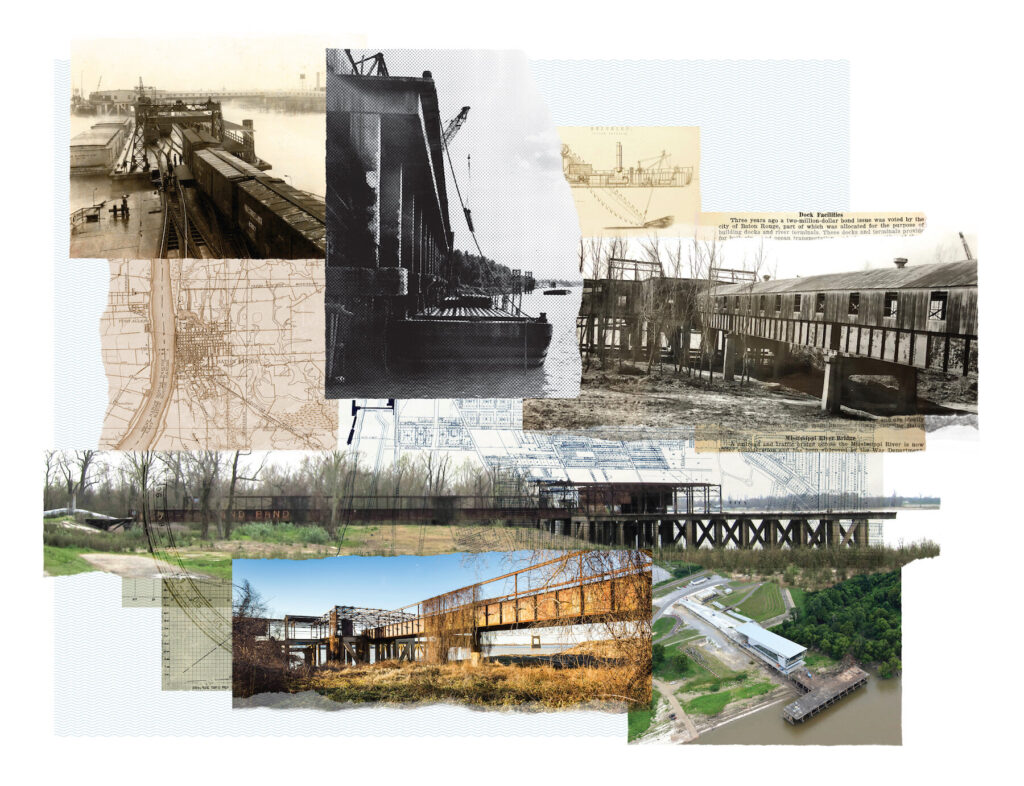

The old dock served as a busy, working wharf for almost 40 years, even retaining a thin stream of barge traffic after the grand new port opened across the river, siphoning off most river commerce. But soon after, it was completely decommissioned and began to fall into disrepair, deteriorating more and more to become a destination like old abandoned “haunted” houses. This continued until 2018 when the Center for Coastal and Deltaic Solutions, which houses the Water Institute of the Gulf, rose on the site, incorporating the abandoned dock as its welcoming front porch.

Standard Oil births an idea

The story of the old municipal dock unofficially began with the opening of the Standard Oil Refining Company’s plant in 1909, right on the Mississippi River just north of downtown Baton Rouge. Standard Oil boasted modern docks and wharves able to receive oceangoing vessels from around the world. In fact, thanks to Standard Oil’s presence, the following year Baton Rouge was designated a port of entry for foreign commerce, enabling international ships to skip a stop in New Orleans on their way up the Mississippi.

Baton Rouge was (and still is) the farthermost point upriver on the Mississippi with a deep-water channel maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; it’s approximately 230 river miles above the Gulf of Mexico. When Standard Oil arrived, the state capital’s own riverside offered only a sloped mudbank and a few wooden wharves and moorings, primarily at the foot of Florida Street; cargoes were all loaded and unloaded manually. It was still very “19th century.”

In 1922, representatives from the U.S. Shipping Board, Mississippi Valley Association and a Pittsburgh bank arrived to investigate the possibility of Baton Rouge becoming an inland port capable of servicing small oceangoing vessels and barges. There was great potential if the city were to build a modern dock, they counseled. By the early 20th century, the federal government had sought to improve inland waterway traffic and, after World War I, had invested in barge lines to compete with expanding railroads.

Location matters

The visitors noted that barges passed Baton Rouge daily and, with no place to dock, continued downriver to New Orleans, then returned the freight to Baton Rouge by rail. A modern municipal dock, with wharves and warehouses and intermodal exchanges for cargo from barge and ship to rail and trucks, would be a great addition.

Baton Rouge was so well-located as a distribution center for all points on the compass—connected by inland waterways and by rail—that cargo movers would save 80 miles by rail and 130 miles by barge, compared to using the port of New Orleans.

Supporting the idea for development of a Baton Rouge port, The Advocate editorialized that “very few persons know that Baton Rouge outranks San Francisco as a port. (Baton Rouge) is the seventh largest port in the United States.” (The editorial didn’t happen to mention that this was almost entirely because of Standard Oil.)

“The proposed municipal dock to handle river trade will be an important contribution to the new industrial era of the lower valley,” the editorial concluded.

Mr. Billingsley is in charge

The Chamber of Commerce and city fathers were duly enthusiastic and included funding for construction of a modern dock in the next municipal bond issue, along with improvements to the abbatoir, library and fire station.

The new facility would be intermodal and up-to-date, able to service barges and ocean-going vessels and, a local business leader projected, would fill the riverfront with ships so that “Baton Rouge (would become) the headwaters of deep-water navigation for the Mississippi valley, just as God and nature intended it to be.”

The 1923 bond issue passed with $350,000 earmarked for the dock. A planning committee was formed to determine what type of facility was needed, and its location. Chamber businessmen (a hotel owner, the owner of a dry cleaner and laundry, a banker, a political scientist, and others), representatives from the City Commission Council and structural engineers comprised its memberships. Representatives from barge lines and from railroads that served the city were consulted and offered tentative commitments to use the new dock. Respected New Orleans civil engineer James W. Billingsley, who had studied river terminals, was selected to direct the project.

Billingsley emphasized that the docks should be planned with an eye to expansion and should target barge traffic as well as ocean-going vessels: “Standard Oil had shown the way,” he told the committee. “You are a natural gateway to the east and west…Your city will enormously increase its activities and your prestige and material welfare will be enhanced manyfold.”

The new municipal dock would represent Progress for the Capital City with a capital P!

The big mistake

In hindsight, however, it seems clear that an important perspective was missing from the planning committee because no representative from the Corps of Engineers, an ocean-going shipping line or even Standard Oil was included. That meant that no one on the committee had firsthand experience regarding the docking requirements of oceangoing vessels, that they needed a deep-water mooring, because of their deep drafts.

The deep-water channel at Baton Rouge had maintained a consistent course since the 1880s: it swirled around the bend at Southern University, sliding down the east bank (past Standard Oil) to just above where the I-10 bridge now stands, then flowed to the center of the river and crossed to the west bank, a bit upriver from where the Port of Greater Baton Rouge is now located.

The deep channel (maintained in 1926 to 35 feet) did not return to the east bank until downriver from the LSU campus, near the tiny community of Burtville. Furthermore, a shifting, sandy shoal had plagued the east bank of the river from downtown Baton Rouge to LSU since 1880.

In April 1924, a representative of the Mississippi Warrior Barge Line, one of the newly developed federal lines, and Billingsley joined members of the dock committee to begin inspection of proposed sites for the new project. Meanwhile, a representative from a barge line had also dangled the prospect of his business operating the facility in cooperation with the city.

A newspaper article specifically stated that multiple sites were to be considered by the committee, though, despite extensive research, I could find no record of what these tracts were. It was therefore a surprise (to me, anyway) when the next reference the newspaper made to the new municipal dock was a December announcement of the selected site: the Southport Mills property. This 7-acre tract near the city’s southern limits was purchased for $75,000 and was the site of a defunct factory that had processed cottonseed, then coconut oil; it was owned by Messrs. Goeghegan and Monsted of New Orleans and was across the river from the deep-water channel, instead situated on the riverbank susceptible to the shifting sands.

Curious about what other properties might have been considered, specifically those on the deep-water channel north of downtown between Standard Oil and Southern University, I consulted a 1923 city map. Although there appeared to be expansive, undeveloped river frontage upriver from Standard Oil at the time, perhaps it had already been purchased since the Aluminum Ore Corp. and C.C. Mengel (hardwoods processing) both constructed plants there within the next several years.

Not surprisingly, an October 1925 Advocate editorial cheered the dock’s planned rail and water interchange and its “most excellent opportunity,” adding that “almost without exception the great cities of the world have been situated where inland commerce shifted to seagoing.”

A steam crane moves cargo

Billingsley presented the committee with his plans—a fireproof, concrete and steel dock, with a 600-foot long platform from levee top to wharf’s end, seeming to ensure accessibility for deep draft ships. The dock itself would sit on 90-foot tall cement pilings that would be, according to the report, driven 35 feet into the river bed by a pile driver barged downriver from St. Louis. His plans were accepted.

A ribbon cutting planned for November 1925 had to be postponed; then it was reported that the first units of docks and terminals would be completed early in the new year.

Shortly thereafter, Baton Rouge Mayor Wade Bynum admitted, “we knew nothing about docks when the project was first considered…but we wanted to take advantage of our natural opportunities on the river.”

More infrastructure was required, so a second $300,000 bond issue was introduced to expand the rail and river interchange.

Construction of the docks was completed in the first half of 1926. According to local boosters, they were the only docks in the world built to withstand the rushing torrent of the Mississippi River. The structure itself combined a quay-type wharf and a floating wharf comprised of barges moored to slide up and down against mooring pilings.

The pier itself, over 300 feet long and 60 feet wide, stood almost 50 feet above low water. An enclosed shed along much of the deck left an adequate perimeter apron for loading and unloading cargo around it.

At the end of the T-head, a locomotive steam crane with the flanged wheels of a boxcar glided along rails and loaded and unloaded cargo, while on the downriver end of the T-head, a static crane serviced barges.

Cargo from the barges moved up an escalator to the long ramp leading from the dock to the warehouses and railroads across the levee. This escalator responded to the river depth—steeply angled when the water was low, lying almost flat in high water. (River levels could differ by as much as 48 feet between high and low water.)

The one-lane steel bridge from the levee to the concrete pier was built with plates and rivets. It was “old style construction,” noted 21st-century architect Buddy Ragland, whose firm, Coleman Partners Architects, led the design team for a new levee-top building in 2014.

Several trucks (approximately the size of today’s pickup trucks) could park simultaneously on the T-head but only one vehicle at a time could drive up or down through the shed.

The first shipment

It was a red-letter day on Aug. 27, 1926, when the first formal shipment arrived: 5,000 bags of rough (unprocessed) rice. These were transferred by “special automatic loading apparatus” (in testimony to the dock’s modernity) and stored in the warehouses, for distribution to local millers.

By December, “record cargoes of steel, cotton and general cargo (household goods, groceries, etc.) clog the docks,” The Advocate reported. And the Chamber of Commerce ran an ad for the new terminal touting its advantages for ocean-going vessels year-round, excellent rail service and connections, river and federal barge lines. It also noted, “Skilled and unskilled labor always available.”

In early 1927, an editorial extolled the “untold volume of freight” handled at the municipal dock. A packet line began semi-weekly service between Baton Rouge and New Orleans and, in April, during the Great Flood, the municipal dock was often used to transfer rescue supplies for victims. In June, the first two ocean-going steamships arrived. They were under contract by Standard Oil to haul asphalt to Rotterdam, and Baton Rouge residents were invited to a celebration complete with music (furnished by the Standard Refinery band), addresses by local dignitaries and an invitation to visit the docks.

A committee from St. Louis arrived in late summer to inspect the unique dock construction, noted “to withstand one of the most adverse tide and current combinations in the world.”

Billingsley had indeed engineered for the challenges of the Mississippi River current, as Buddy Ragland discovered when his team first inspected the dock’s pilings and decking: almost 90 years after its completion, the pier remained surprisingly structurally sound.

Daily maritime traffic continued to keep the dock bustling. In addition, it was where the public flocked for touring ships that stopped on goodwill voyages, such as the restored U.S.S. Constitution (Old Ironsides) and the destroyer, U.S.S. Schenk.

Tonnage at the municipal dock continued apace and in 1936 the city leased the dock to Federal Barge Lines for 12 years. Two years later, total tonnage was reported to have increased by 91% over the past decade’s annual averages, indicating “that local shippers are taking advantage of the cheaper water transport rates” to move case beer, canned goods, iron and steel, soap, automobiles and more. “Several local chain stores get all merchandise by river,” the newspaper reported.

In the small print, worrisome information

In 1947, the port of Baton Rouge recorded its largest tonnage since 1926, but the small print of the report revealed a problem: Not only did the statistic reflect operations at all area docks including Standard Oil, the Solvay docks and the Texas Company’s loading station but also that tonnage at the municipal dock had showed a decrease.

This was followed the following year by Federal Barge Lines allowing its lease on the dock to expire, with removal of their freight-handling equipment.

This “left the dock in a state of partial disrepair” as its administration reverted to the city. This led to creation of the Baton Rouge Port Authority.

The new authority was almost immediately faced with the large expense of dredging around the dock, to remove silting that prevented even barge traffic from accessing the pier. It had also become sadly apparent that ocean-going ships, with drafts even greater after World War II, could only moor two or three months a year, when the Mississippi was high. In fact, during the previous year, the authority admitted, 10 ocean-going vessels had landed, but 16 had been turned away because of low water.

Still, Baton Rouge had a preeminent location; it remained the farthermost point upriver on the Mississippi accessible to ocean-going vessels with the advantage of access to the Intracoastal Canal and several rail lines. By 1951, all concerned were forced to admit that the municipal dock had primarily serviced barge traffic since the mid-1930s and dredging was a continuous challenge.

Furthermore, the Baton Rouge Port Authority had limited jurisdiction over any riverfront but the dock and lacked the resources to construct and operate a modern inland port to attract ocean-going vessels and global traffic as well as barge traffic from the inland waterways.

The authority had distinct limitations, so it was hardly surprising when New York engineering consultants Knappen-Tippotts, Abbett McCarthy publicly observed that the Baton Rouge area was missing its potential to handle several million more tons of cargo, a goal that could be achieved with the creation of a public port operated on a regional basis.

Go west, Port Authority

Once again wafted the tantalizing whiff of progress with a capital P.

The consultants wisely recommended locating new docks and terminals on the west bank just below Port Allen, where land for future expansion was available and the deep-water channel nuzzled the bank. No east bank option existed except at Burtville again, which was deemed too far downriver from the urban complex.

Through the complicated mechanics of the state legislature and voters, the Greater Baton Rouge Port Authority was created in 1955. The new entity would have jurisdiction over river docks not only in East Baton Rouge but also in West Baton Rouge, Iberville and Ascension parishes. But in October 1955, even before the bonds were sold and the new port constructed, the new port commission agreed to lease the old municipal dock for 10 years, rent-free, promising to continue to operate and maintain it as a public facility for barge traffic. It was, after all, an asset within their geographic purview.

Unfortunately, the problem of silting persisted and the city and port commission began to argue about which entity was responsible for maintaining river access; no specific language had been included in their agreement. The port commission shrugged off the responsibility—dredging and removing silt wasn’t maintenance, they argued, while an editorial intoned that “the dock, in usable condition, is an important asset to the city.” It hoped the dock’s utility would be maintained, by someone.

By then, however, another new barge facility, opened by the port authority, had been built north of the city at Devil’s Swamp and locals complained that the port commission was treating the old dock like a stepchild. “They haven’t as much as put one bucket of paint on the Municipal Dock,” complained a city councilman.

In September 1957, The Advocate reported that a mudbank or shoal had built up along the east bank from just south of the Esso (formerly Standard Oil) plant to the LSU campus. The shoal had created “problems for the ferries and for industries and waterfront interests on the east bank and seemed to have little to do with the river level.”

The area around the municipal dock had again silted up. Barge traffic to and from the dock was viable only when tugboats with their powerful motors could spin open an access channel.

The disagreement between the port authority and the city about dredging finally came to a head when an Ethyl Corp. tow (the configuration of multiple barges lashed together) could only access the old dock when the company’s tug churned a channel through the silt.

The port commission shrugged off responsibility and Ernest Wilson, its president, reminded the city council that the Greater Baton Rouge Port Authority had exclusive jurisdiction over all common carrier water traffic in the four-parish area, including East Baton Rouge. If silting made the old dock unusable, he offered, barges could simply use the Devil’s Swamp facility. And besides, the old dock was losing money.

“The (port) commission saying they won’t maintain the dock and won’t permit the city to operate it is disturbing,” opined a September 1960 editorial. “The public might like some reassurance that the dock is not being deliberately neglected in an effort to persuade local shippers, somewhat against their will, to use other facilities and that abandoning the dock would not affect shipping rates adversely.” The old municipal dock had by then become known as the East Bank Barge Dock.

To no one’s surprise, the port commission did not seek to renew their lease on the dock, so authority for it reverted to the city. They began to search for a new lessee until the Kiwanis Club, working in conjunction with the city beautification commission, asked to include the old dock as a visitor attraction within its plan for a total riverside restoration. The dock structure, described as dilapidated and shabby on the outside, “but its piers, floors and timber are still good,” would be worth fixing up as a viewing site for construction of the new (I-10) bridge and for a scenic, public river overlook.

Gatherings, both legal and not

In September 1964, with suitable fanfare, the newly renamed River View Docks opened to the public for visitation on Saturday and Sunday afternoons from 1-6 p.m. Safety fencing had been added, the batture cleared to allow for parking and picnic areas, and a new covered walkway, enhanced with potted trees, extended to the end of the T deck. Art exhibits were occasionally held there and organizations sometimes rented the space for a dramatic venue for parties and crawfish boils.

But these activities weren’t sufficient and contributed little to city coffers, so the city-parish council began to seek proposals for re-use of the property. A parade of prospects appeared between 1975 and 2010: a themed restaurant sited on the T-head; the home base for a tour boat company; a repositioned 1927 steamboat, General Robert E. Lee, as a restaurant and bar situated on top of the dock (the steamboat was actually placed on the dock but ultimately removed and towed to Biloxi); lease to a marine repair company; use as a riverboat casino mooring; a mixed-use development with offices, a cultural center and restaurant; another, more futuristic mixed-use development with river-view residences, restaurants and a grand plaza.

The dilapidating old dock also presented a creative challenge for students in the LSU landscape architecture department looking for thesis topics. None of the plans materialized and, most ignominious of all, in 1990 when the new paperclip dock was built near the U.S.S. Kidd, the city designated it as “the municipal dock.”

Time covered the old municipal dock with an increasing patina of neglect and despair. Vines tendrilled through the rusted metal sheds; corrosion chewed holes in the sheet metal decking; the rusted skeleton of the fixed crane loomed like a wreckage.

But the decay also transformed the dock into a place of allure and adventure, attracting a constant, though illegal, parade of visitors like the “Imagine” painter who wended their way past the obstacles to the end of the pier.

Young people, both black and white, sneaked out after dark, past the “do not enter” signs, to drink, cuddle or just sit and watch the river. Fraternities were known to leave underwear-clad pledges there and homeless people built cooking fires with the plentiful driftwood from the batture. At least one local band sneaked out to record its edgy music video, and LSU photography classes arrived to shoot the visual spectacles of the building and the river.

Even a few professional photographers confessed to me that they had sneaked clients past the barriers—businessmen and brides, mostly, to pose against the vivid graffiti of the shed walls or the riverscape. One swore the old dock offered the most brilliant sunsets available to locals.

Back to the river

Not until December 2013 did the old dock’s grand finale occur. The Baton Rouge Area Foundation announced that the “longtime eyesore in downtown Baton Rouge” would become part of The Water Campus, which was envisioned to lead in coastal education and big data research, to help improve the way the world uses its water resources and adapts to rising seas.

The location on the river would emphasize their dedication to water. The Center for Coastal and Deltaic Solutions, the first building on the campus, broke ground in November 2015.

“We intended to build on the old dock,” Buddy Ragland confessed of its unique setting, “but the cost and logistics, of testing the dock’s structural integrity was prohibitive” and no structural renderings of the pier had survived. So the architects designed the CCDS building to perch above and across the levee with the old dock laid out before it as a river overlook.

They cleared the dock to create an open space and removed all remnants of both original sheds and the 1960s additions. But relics still remain that recall the dock’s 1926 promise to the city: The tracks of the old locomotive crane rip through the deck at pier’s edge, and the downriver end of the T-head is decorated with the rusted, geometric bars and gears of the static crane. Also, the 1980s “Imagine” lyrics remain, though barely legible on the old concrete deck.

The murky boil of the river still rushes under the pier in high water, and, when the water is low, waves dapple the sandy bank, slapping softly and settling the batture with driftwood and debris from somewhere upriver.

It’s the “new” old municipal dock, one of the best places around to appreciate the river, our history on the Big Muddy, and the power of re-imagining.